Black History Month draws global traveler to metro areaBy MONI BASU As a young lad, Ian Hall was challenged to learn how to play the piano over the summer holidays. "Ian Hall, still a playboy, eh," his teacher at Archbishop Tenison's Grammar School scolded the 14-year-old. "No serious effort." By the time school started back up, the self-taught black teenager from the colony of British Guyana (now Guyana) astonished his teachers at the elite London school. "I was playing the preludes and fugues of Johann Sebastian Bach," said Hall, 63. "I was at the piano day and night." To say that classical music changed the course of Hall's life would be an understatement. It became a vital thread that bound all his passions together. |

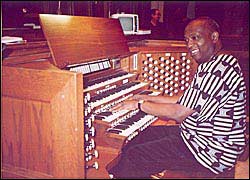

Ian Hall sits at the organ at Episcopal Cathedral of St. Philip, where he performed in November. His love of music is the thread running through his work for peace and racial harmony. |

It even helped him earn a job as an unofficial global ambassador of sorts. U.N. Secretary-General Kofi Annan tapped Hall three years ago to head a new network of charitable organizations -- World Association of Non-Governmental Organizations, or WANGO -- that was part of an effort to clean up the waning reputation of the world body.

"WANGO has been an important image-corrective for the U.N.," said Hall, in Atlanta for Black History Month events. "We concentrate on the Third World. We are calling for a culture of peace and nonviolence."

The son of a Royal Air Force flier, Hall abandoned family hopes of his becoming a doctor, instead focusing on mastering the organ. He is believed to be the first black graduate of Oxford University's prestigious music school. He went on to compose masterpieces and played in the world's finest halls.

But he was always keenly aware of the color of his skin and of the monochromatic nature of his upper-crust schools and performance hall audiences. Inspired by the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and the civil rights movement, Hall set about to splash a bit of color in the largely white world about him.

A new 'racial harmony'

Shaken by King's slaying in 1968, Hall conceived the Bloomsbury International Society, an institution that helped Hall marry his musical talent with his desire to keep the civil rights leader's dreams alive.

"My real thing in life has been promoting racial harmony through the arts," Hall said in his perfect queen's English. "Most people respond warmly toward one another in an atmosphere where beautiful music prevails."

Hall began orchestrating multicultural performances that twinned classical Western instruments with sounds from the Caribbean, Asia and Africa.

Sitar met violin. Westminster Abbey resounded with the twang of the Ebony Steel Band. And the Commonwealth Institute marked its golden jubilee with Queen Elizabeth II in the audience and the thumping of Ashanti drums accompanying baroque brass on stage.

"Most events in well-known venues used to be sedate," Hall said. "Lugubrious, really."

At his nephew's suburban home in Fayetteville, Hall relaxed in burgundy sweats with a cup of coffee warming his hands. The kitchen table was a far cry from St. Martin-in-the-Fields or the Achimota School in Ghana, where Hall spent years as music director.

Yet Hall seemed just as comfortable here. In between his thoughts on Atlanta's appeal as an international city, Shakespeare rolled off his tongue with the greatest of ease. "Music is the food of love," he said.

Three decades of intercultural music gained fame for Hall -- his part nobleman, part colonized persona appealing to a broad spectrum of people.

A quick journey through the pages of his photo albums turned up familiar faces: Nelson Mandela, Tony Blair, Queen Noor of Jordan, Desmond Tutu, former U.N. human rights commissioner Mary Robinson. Hall "hangs" with the Rev. Al Sharpton just as easily as he does with former British Prime Minister John Major.

In 2000, Annan called on Hall for a job that seemed a perfect fit in Hall's musical mosaic of goodwill and harmony. Annan's massive reforms at the United Nations included the formation of an independent group of nongovernmental charitable organizations around the globe.

"It was Annan's idea," Hall said of the organization that came to be known as WANGO. "He wanted dramatic reformation, but not through governments. It was a short jump for me from Bloomsbury to NGOs [nongovernmental organizations]. The only difference is that Bloomsbury is more artistic."

Waking the young

Sixteen international agencies came together to form WANGO, a network that pledged to promote the ideals of the United Nations and the ideals of peace, justice and well-being for all of humanity.

WANGO, now with 450 varied members, meets every October to share ideas.

"Most governments are vagabonds. They are corrupt," Hall said. "NGOs should play a bigger role. Their aim is not self-aggrandizement; their aim is to serve the people."

To generate support and build his organization's membership, Hall spends a good bit of time traveling and recruiting eager hands ready to help the disadvantaged. He also promotes an international Slavery Memorial Day and Human Rights Day, both in December.

He decided to spend Black History Month in Atlanta, the home of the civil rights movement.

"I want to take King's legacy forward in the most practical and idealistic way," Hall said, recounting an incident not long ago when two black teenagers in London stopped the conversation cold to ask, "Was King black or white?"

"King's gone to sleep a bit. Of course, he's big news here in Atlanta, but in the rest of the world, he's not," Hall said. "We have to figure out a way to repackage him for the younger generations."

King's ideals, said Hall, fit in perfectly with every single one of his life missions, including WANGO. While in Atlanta, Hall said, he was anxious to meet with Coretta Scott King, philanthropist Ted Turner, Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter and Peter Bell, the president of the relief agency CARE USA.

When he was here last November, he played at the Episcopal Cathedral of St. Philip in Buckhead. He wants to take primarily black Morehouse students to mostly white St. Martin's Episcopal School.

"I want to bring all these people together," he said. "I'd like to see a world where we can approach each other with the utmost charm. The Garden of Eden -- I've seen glimpses of this."

An idealist, perhaps, at heart? "Of course, I am," exclaimed Hall, a broad smile filling his face. "To express the ideal is, after all, the height of nobility."